Prologue

For brevity “YU-NO” suffices though it hardly encapsulates the maximalism of the thing, spellworked across fifteen legendary floppies or packaged into the quaint 21st-century promise of one CD. So you may after all want at least once to fall back on the entire name, just to know what it tastes like. YU-NO: The Girl that Chants Love at the Edge of the World is the name of the 2011 fan translation of the game. An achievement with ambition to match the source material, it remains the most impressive videogame fan translation project to date. There are other translations of the original Japanese title この世の果てで恋を唄う少女YU-NO, such as the official YU-NO: A Girl who Chants Love at the Bound of This World (果て = “end,” “bound,” “extremity”).

“Just to know what it tastes like.” YU-NO is long. Ridiculously so when you consider when and into what landscape it arrived. For 100% completionists, YU-NO is a 100-hour game. I have played YU-NO to 100% completion. It took three years. Most of that time I spent not playing YU-NO. Most of that time I wasted as easily as if it belonged to someone else. I began YU-NO in December 2019, back when I knew so much less but understood so much more. By the end of December 2022 I had finished YU-NO. I had taken the long way around. My in-game time did not count my false start that fizzled out somewhere around February 2020 nor the August 2022 da capo I needed to see the game through al fine. It simply read “89:07:25.” YU-NO is a 100-hour game. Most of those 100 hours are spent clicking the screen to advance dialogue or to examine points of interest at your leisure. YU-NO demands no dexterity, expects no acuity. It doesn’t take reflex; it doesn’t take intellect. To see YU-NO through takes nothing more than patience. All you need is dedication. All YU-NO takes is time.

YU-NO

YU-NO is an adventure game developed and published by Elf and released on December 26, 1996 for NEC PC-98 series computers. In 1997, a version of the game was released for Sega Saturn, and in 2000, a version was released for Windows PC. Between 2017 and 2019, a full remake was released for PlayStation 4, PlayStation Vita, Nintendo Switch, and Windows PC via Steam.

Set in then-contemporary Japan, YU-NO follows the adventures of honor-student-turned-delinquent Takuya Arima, son of infamous fringe historian Koudai Arima. Shortly before the game opens, Koudai goes missing and is presumed dead. The game takes place in the aftermath of Koudai’s death, over the course of four days in the summer of Takuya’s final year of high school. Though he would never admit it thanks to the adversarial relationship he had with his father, Takuya is taking Koudai’s death hard. Once an academic achiever and star athlete, Takuya has become a misfit, hedonism his armament and apathy his shield. He has relinquished his captainship of the school’s kendo team and spurned his former friends. He picks fights he knows he can win. He picks ones he knows he can’t. Summer break is starting and he has remedial classes. He doesn’t plan to attend.

As in many classic Japanese adventure games, YU-NO deemphasizes puzzles and inventory management, at least initially. Instead it places a heavy premium on following a linear story and communicating with its cast of characters.

As summer begins, you meet these characters, converse with them, come to understand who they are. Slowly you learn that everyone has a secret.

Koudai’s is that he isn’t dead.

“By the time you read this letter, it is likely that I have already concealed myself from you. But this serves not as an indication of my death.” Takuya grips the impossible letter in trembling hands. It arrived unexpectedly, on his first day of summer school. It’s no more than a note. But it’s real. And like its scribe himself, Takuya can hardly make heads or tails of it.

“You must realize that the passage of time exists not as an irreversible, but reversible concept,” Koudai writes. “But wouldn’t that imply that it’s possible to recreate history…? That’s not quite right. History is an irreversible concept.”

The letter rattles on like this, elliptical to a fault. What it means is unclear. All that it explains in concrete terms is that Koudai has embarked on a journey. Later, you discover the purpose of this journey. Later still, you learn that it has swept Koudai to the limits of human understanding and beyond. For now, all you know is one thing.

He wants Takuya to follow.

Its designer

YU-NO was designed and written by Hiroyuki Kanno (1968–2011), a game creator whose name you may still hear whispered if you know where to listen.

Prior to the development of YU-NO, Kanno worked first as an employee at — and subsequently as a freelancer with — eroge developer C’s Ware. There he designed pornographic adventure games like Love Potion (悦楽の学園 [“School of Pleasure”/”Pleasure Academy”/something to that effect]), Desire, Amy’s Fantasies (エイミーと呼ばないでっ [“Don’t Call Me Amy”]), and most famously Eve: Burst Error.

After the release of Eve, Kanno was personally invited to join Elf, one of the most prolific adult game developers in Japan at the time, where he began work on YU-NO.

Following Eve’s biblical motif, YU-NO employs a point-and-click adventure gameplay system called the Auto Diverge Mapping System, or “A.D.M.S.”

アダムスと読みます explains the game’s original manual. “Read as ‘Adams.’” (By the way, my Japanese is extremely basic, so any corrections if necessary are welcome.)

The finale of the game employs imagery to match, a man and woman naked under a tree in an endless green paradise.

But first, you have to get there. The A.D.M.S. is how you do it.

Its play

Alongside the letter from his father, Takuya receives two items: a mirror that belonged to his mother, and the Reflector, a strange device that enables its user to travel through time, powered by eight Jewels. “There is no meaning,” Koudai writes, “if all eight Jewels aren’t fitted into it.”

They aren’t. Only two Jewels are set into the device. The other six, Takuya eventually finds out, are scattered across space and time. Once you find them, you will be able to track down Koudai, uncover the mystery of his disappearance, and discover at last what’s really going on. With no other choice but to believe that this is true, Takuya sets out to find the other six Jewels.

What I have just finished describing is a heavily abridged version of the game’s prologue. Today, most Anglophone articles about, videos covering, discussions of, and references to YU-NO erroneously label the game a “visual novel.” YU-NO is not a visual novel. It’s an adventure game, and a rather traditional Japanese one, at least to begin with. As Takuya, you click through menus of verbs and nouns to navigate through and interact with the game’s world, proper to YU-NO’s genre. Text displayed in a window near the bottom of the screen recounts dialogue and the protagonist’s monologue, commentary, and introspection. During the prologue, all of this plays out in a linear manner, with little player interaction besides choosing menu options.

But once the prologue ends, things change.

The first change you notice pertains to the game’s interface, which at the game’s modest outset looked like this…

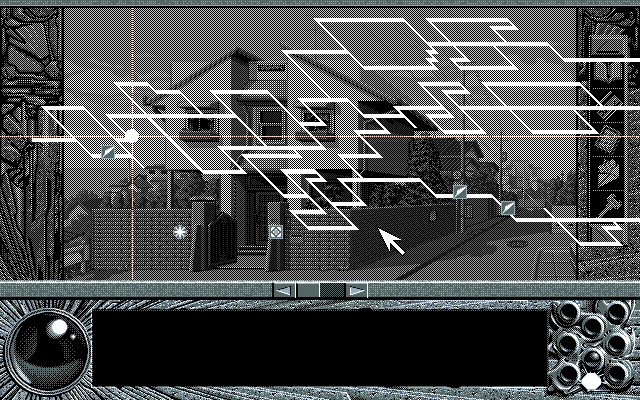

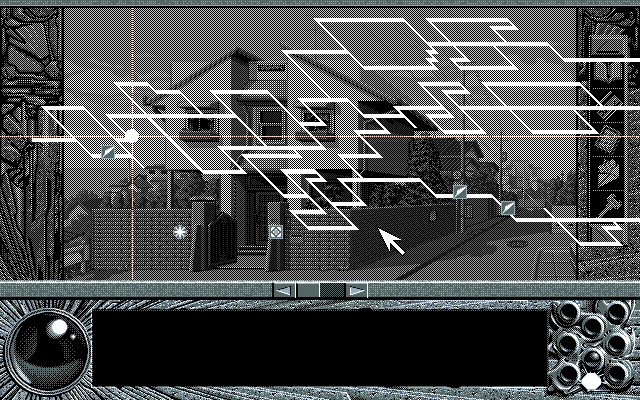

…but that now looks like this:

The game communicates the end of its prologue rather plainly through this change of interface. Playing diligently, you have spent perhaps upwards of three hours to arrive at this point. This is the moment at which, if you didn’t know it prior to starting, you begin to suspect that YU-NO might be a 100-hour game, though at this point you would be forgiven for ballparking it at a safe 50.

The second change you notice when you move your mouse. Once confined to the rectangular menu in the corner (not pictured in the screenshot above), your cursor now has free reign of the screen and may, depending on where it hovers, display a number of different icons, each corresponding to an action:

Nor are these changes merely decorative. They reflect a pole shift in the system that undergirds YU-NO’s adventure gameplay. Following the prologue, YU-NO transforms from a traditional Japanese adventure game — often linear, character driven, based around prescribed choices — into a sprawling point-and-click adventure replete with items to collect, puzzles to solve, and a deceptively sleepy seaside town whose secrets await uncovering.

Of course the aim of this game of point-and-click is the same as Takuya’s aim: to find the remaining Jewels that power the Reflector.

Here is how you do it.

1. Use the mirror to go back to the beginning

On the left side of your screen, an array of ancient grooves screams into a large circular button. This is the mirror that belonged to Keiko, Takuya’s mother and Koudai’s first wife. “Consequently, this strong connection to your real mother will become the trigger to tightly bind you to that place,” Koudai explains in his letter. Clicking this mirror not only allows you to save the game and return to the main menu at any time but also to return to the beginning of the “main game” (the end of the prologue when Takuya first gains use of the Reflector) at any time as well.

You see, whether he likes it or not, Takuya has, in his search for the Jewels and his father, become an investigator; some have greatness thrust upon them. Naturally he will reach an impasse in his investigation, eventually. But coming to a dead end is not Game Over for Takuya. When you are stuck, the mirror is your instant retry button with infinite continues. It will even save you from a literal dead end: death.

Like Death Stranding’s “repatriate” protagonist Sam, Takuya keeps coming back. He will not, in fact cannot, fail as long as he has his mother’s mirror. When he fails, he simply goes back to the beginning to try again.

2. Use the Reflector and Jewels to travel through time

Opposite the mirror is a series of items, each of which plays into one or more of the game’s puzzles.

Underneath is the Reflector inlaid with Jewels.

Once Takuya collects all eight Jewels the path to Koudai will open for him, but until then the Jewels serve another purpose. They act as bookmarks across the game’s sprawling spacetime — your “save states” (the game even calls them this).

Wedged in with the Jewels is a button at the bottom of the Reflector whose press displays a map. As long as you have even one Jewel you can view this map at any time:

This is not a map of space. It’s a map of time. Depending on where you go, what you do, and to whom you talk, Takuya’s summer vacation will follow a different timeline, take on a different narrative form. While these timelines all stem from the same origin, they quickly become distinct. One, for instance, follows an inspection into the school’s enigmatic headmaster Ryuuzouji. In another, Takuya investigates Geo Technics, the shady research institute at which his stepmother Ayumi works.

Each parallel world branches out based on the decisions you make and each too contains clues pointing at the overarching mystery. Collect these clues and you will begin to piece together a picture of where and to what ends Koudai has journeyed, and how to collect the items you need to find him.

YU-NO gamifies this investigation via the previously mentioned Jewels. At any point, you can click one of the Jewels in your possession to leave it behind and mark your place in time on the map, like this:

If later on you need to return to this time to collect an item or follow a different path, simply open the map and click on the placed Jewel. Takuya will instantly warp back (or forth) and the Jewel will be returned to the Reflector, ready to use again when you need it.

In this way YU-NO’s gameplay builds a positive feedback loop. The Jewels are lost in both space and time, so finding one requires you to be at the right place at the right time. As you journey down different timelines, you solve puzzles to recover the missing Jewels. Sometimes these puzzles are straightforward and sometimes they’re not. Sometimes they require items from across multiple timelines. Create “save states” with Jewels to jump back and forth between timelines, collecting the items and gathering the intel in one timeline you need to proceed down another. The more effectively you use the Jewels you have, the more efficiently you will be able to collect the ones you lack. The more you collect, the more capably you traverse time, a clean positive feedback loop erected atop an adventure-game foundation.

These are the basics of what the game calls the A.D.M.S.

Protected by your mother and empowered by your father, you are ready to begin your Jewel hunt.

Its players

There is an excellent if occasionally misguided essay about YU-NO, in fact the only lengthy one I can find in English, called Time Traveler’s Diary. There is the link if you are so inclined.

One of the most interesting points that this essay brings up is the relationship between YU-NO and the concept of “possibility space” in video games.

Possibility space refers, the piece explains, to “how the range of possible strategies and playstyles expands and contracts as a result of a game’s rules, however simple or complex.”

YU-NO, the piece recognizes brilliantly, maps its own possibility space in a way that few games can and fewer yet dare, with no deceit. It’s right there, on the map, for you to trace as you play, and in fact tracing these potential spaces — seeking out all possible shapes that the game can take and mapping them — is the game of YU-NO itself.

Though your goal in YU-NO is to collect the Reflector’s missing Jewels, the completion percentage attached to your save file measures neither how many Jewels you have collected nor how many items, or even how many of the game’s numerous endings, good or bad, your decisions have wrought.

Instead it tracks how much of the game’s map you have uncovered:

Each action you take ushers you further along in time. Each stretch of map and each node at which the path branches corresponds to a possibility in time, one potential iteration of the world of YU-NO derived from the decisions you make as a player and their consequences.

In this way, the piece explains, YU-NO comes to represent diegetically the character of nearly every video game in the lineage of the art beginning from its inception: a nonlinear layering of untold possible superpositions.

Take a linear action game wherein to proceed necessitates, for example, defeating multiple enemies in a room. Your initial attempt may involve defeating enemy A first with a combo attack that positions you subsequently to strike enemy B from behind. If this fails, you die and reload. This time, you take a different approach, confronting enemy B first.

These are only two possible resets, two possible worlds our hypothetical game may produce in feedback to the player according to its rules. Depending on the game’s complexity, the total of possible iterations may quite literally take more than the entirety of your waking lifetime to see if to do so were your aim — and that’s just one combat encounter out of (hypothetically) many.

Of course as an adventure game, even a 100-hour one, YU-NO’s possibility space is far more limited. In truth it is frightfully slim, deceptively so given the game’s staggering spacetime story map. The game’s state changes only when you take action. But this is what YU-NO asks you to do: witness and chart all of it. Only completing its map of all possibilities will reward you with 100% completion.

Another example using another game, a real one this time, to explain: Policenauts revolves around following a linear narrative whose dialogue changes slightly in response to player decision and action. The aim of Policenauts is nothing more than to see the story through to its end by interacting with the game’s characters, investigating its maps, and occasionally shooting. But if Policenauts were like YU-NO, then the goal of the game would be to trigger and map every possible permutation of dialogue and the game would hinge ultimate narrative payoff on so doing.

If accomplishing this sounds improbable, then extrapolate the logic outside of the adventure game paradigm and it begins to sound impossible. Suppose the action genre again, this time implemented in an expansive and systemic open world: what if in a game like Grand Theft Auto V or The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild the ultimate goal were to trigger at least once every possible state corresponding to which the game could exist programmatically?

You simply couldn’t do it. The field of play is too wide, the expanse too broad.

In YU-NO it is possible. YU-NO is a pure adventure game so naturally concerns no action or systemic interplay. Moreover it is a 2D game in the point-and-click mold, with largely static visuals and no onscreen character movement except for minor animations such as blinking. Outside bugs and crashes, pure game design describes and circumscribes its play. Its potential states are therefore entirely prescribed.

What this means is that its creators understood by necessity before YU-NO ever arrived in player hands every step of the game and every version of its possibility space that its play could ever elicit. They even numbered them. A bulletin board in the lobby of Takuya’s school displays a number that accords to your location on the map, a code corresponding to a splinter in time:

(Actually, Metal Gear Solid 2 does something similar , but only as an easter egg or neat detail.)

In YU-NO you play exactly according to the rules of the game, its prescribed design. Unlike in a systemic game, the program affords you no possibility to do otherwise. This is a game of figuring out how to follow the tracks that were laid out for you in advance, a game about following in some first pilgrim’s monumental steps. “’Time as cage’ is not an irrelevant observation, nor is ‘bounded possibility space,’” the Time Traveler’s Diary essay observes. “YU-NO is a game about fixed boundaries, about immutability. Specifically, it is about fate.” (link mine)

Fate: Takuya continually disparages his, shouts as if to render it unreal. He doesn’t know where he’s going. All he knows is he is following in heavy footsteps.

And he can’t stand who left them.

Kanno’s design and Kojima’s

In a sleight common to the Japanese erotic adventure genre, the 1996 version of YU-NO bangs its protagonist’s face into obscurity; all the better for self insertion. More interestingly, neither does it reveal the face of Takuya’s father.

Whether this is another genre trapping I can’t say, but in YU-NO at least Takuya and Koudai form an interesting pair. “Hope you’re ready, old man. I’m going to find you and when I do I will clock your lights out!” This is not a line from YU-NO, but it might as well be. The son follows in his father’s footsteps with hatred in his blood, cursing his every step. He understands that to aim for Koudai means to walk in his wake, yet wants desperately to chart his own path, to be his own man.

If YU-NO is a single-player game crafted out of pure game design and Takuya is the player character then we might consider Koudai to be his counterpart: the “designer character,” whose missive initiates a mission profane to the ego. Just as Takuya must at some point recognize that he can’t help but follow Koudai’s path, so as well must players admit that we may play YU-NO only in accordance with its design and no other way. Every possibility in this game, after all, has been laid out for us in advance:

In this way I consider Kanno’s design to be a precursor of sorts to Kojima’s. Kojima’s design imbues figures like “Snake” and “Boss” with a metaludic meaning so that they might stand for a game’s player and its designers. The designer of a single-player game, after all, is both the one who lays the traps and hopes with a secret affection that the player will overcome them: a double agent. 1987’s Metal Gear represents this player-designer relationship narratively when it reveals that Snake’s commanding officer and ally Big Boss is in fact the leader of the terrorist faction, an actual double agent within the game’s story. Metal Gear Solid iterates on the idea and Metal Gear Solid 2 hammers at it until it is cynical and bitter and irrevocable. But in YU-NO Kanno dreamed a drama of these same constituents before Raiden and the Patriots were a twinkle in Kojima’s eye. On Kanno’s stage, the designer is no clandestine conductor but a distant father who instead of handing his son the map empowers him to fill in its blanks, far away and proud.

And always just out of reach.

Time and causality

Takuya never finds Koudai.

Instead, once he acquires all eight Jewels, he is transported to Dela Grante, a fantasy land of magic and dragons, whereupon the point-and-click adventure ends and the linear menu-driven gameplay from the prologue resumes.

Like the player, Takuya does not know how he got to Dela Grante nor does he know how to go back to his world. He meets a mute elven woman named Sayless (セーレス, “Celes” in the official translation, though the fan translation “Sayless” communicates the pun). With her he begins a simple life in a cottage that saddles the boundary where a gentle woodland becomes desert. Eventually the two conceive a child, Yu-no. Around 70 hours in, half of YU-NO’s subtitle and its namesake, “the girl that chants love,” reveals herself.

It takes a dozen or so hours more for the other half to do the same.

What follows is a heavily condensed description of YU-NO’s epilogue with some details omitted or simplified for the sake of concision.

Sayless, Takuya learns, is a Priestess from the Imperial Capital of Dela Grante and an escapee. Having forfeited her speech to her religious duties, she disavowed the coming sacrifice of her life and fled to the borderlands where she met Takuya. Through a careless and inadvertent mistake of Takuya’s, the God Emperor, who rules Dela Grante, comes to learn of her whereabouts. Days later, armed soldiers arrive to retrieve her. Takuya struggles against them but is outnumbered and easily subdued. Knowing that there is no hope, Sayless speaks to Takuya for the first time. She tells him she loves him and bites off her tongue.

The player does not miss the irony nor does Takuya accept his loss. He toils across the merciless desert with Yu-no to take revenge on the God Emperor. Along the way he is separated from his daughter and enslaved, but eventually he comes to the Imperial Capital where the ruler resides. He infiltrates the palace walls. Inside, his daughter (note the comma — the commaless version comes later and no, I’m not kidding), now an adult and an imperial knight, has taken on her mother’s duties and will be sacrificed in a matter of days to avert a calamity known as the Wrath of Mother Nature. (There is a certain if uncompelling eco-drama playing somewhere at the edges of YU-NO, but that’s a topic for another time.)

Takuya hides overnight in the palace to confront the God Emperor, catching up with Yu-no in the meantime. In the morning the chance presents itself. Takuya waits in ambush behind a pillar, gripping his sword in anticipation. This is the most suspenseful scene in the game because I understood beyond doubt at that moment that the Emperor who was to walk down that corridor unguarded and whose unsuspecting flesh would meet Takuya’s steel would be Takuya’s father.

It wasn’t.

It was his mother.

His stepmother from his past life, Ayumi.

The castle guardsmen are alerted and comes to their ruler’s aid. Takuya and Yu-no flee. They are saved by the sudden appearance of Eriko, Takuya’s homeroom teacher and school nurse from his life on Earth. In that world, she was a steadfast and unexpected ally of Takuya’s in his search for Koudai, appearing mysteriously wherever needed with knowledge beyond her station. In this world, she at last reveals her true agenda and identity. She is a “dimensional investigator” from a separate world entirely, neither Dela Grante nor Earth, on a mission to apprehend a powerful malignant entity. On Earth that entity posed as Ryuuzouji, the headmaster of Takuya’s school. Now it has arrived in Dela Grante and will before long show its true form.

Takuya doesn’t understand. Eriko explains. In primitive worlds like Takuya’s Earth, humanity is the subject of time, a mere witness to its passing unable to infringe on its flow. But the world she comes from has mastered time and “event scientists” have discovered a dimension that supersedes and encompasses it. That dimension is causality, the flow from cause to effect, and it has nothing to do with time. The process by which past builds into future, Eriko explains, is neither linear nor determined by the passage of time. It is decided by the law of cause and effect called causality, which proceeds irrespective of time.

In the world she comes from, Eriko continues, causality is a science, understood as conforming to known laws of fluid motion, potential energy, and inertia. The field of “event science” therefore studies it as a science, mathematically, and aims to chart its totality, the sum of all possible events, onto a nodal model termed “Vrinda’s Tree” after its rhizomatic structure.

Takuya is lost. How is it possible that causality, which simply means causes engendering effects, can counteract the passage of time? And what does it have to do with this tree structure? Here is a paraphrase of Eriko’s explanation:

Suppose you have the power to travel back in time and are thinking of doing so but decide not to. The sequence of cause and effect looks like this:

You are thinking of traveling back in time. (You are in the present.) → You decide not to do it. (You are still in the present.)

Now suppose the same state of affairs, that you have the power to travel through time and are thinking of doing so. This time you go through with it:

You are thinking of traveling back in time. (You are in the present.) → You decide to do it. (Now you are in the past.)

Time and your hypothetical ability to travel through it are entirely irrelevant. Even a nonlinear experience of time does not escape a linear sequence of causality.

This structure, the shape of cause engendering effect and splintering out into a functional infinity of possibility, is what in Eriko’s world is known as history.

“History.” It’s a familiar word. Takuya and the player alike recall that forgotten inaugural from another lifetime. “You must realize that the passage of time exists not as an irreversible, but reversible concept. But wouldn’t that imply that it’s possible to recreate history…? That’s not quite right. History is an irreversible concept.”

The game displays a diagram of Vrinda’s Tree to illustrate and upon the sight of its mystic architecture you recognize your misapprehension, understand that until now you have been looking at this thing all wrong — that you have misunderstood what YU-NO is about on a fundamental level.

Here as you are reasonably beginning to suspect that the hours on your game clock may tick into the triple digits is where YU-NO finally clicks. All it took was time:

What you are seeing is the structure of the Reflector map, the narrative and ludic structure of YU-NO, ornamented out of its stark minimalism and rotated, but otherwise intact. All along you have been mapping your own small branch of this tree that transcends time. YU-NO, you see, despite everything, is secretly not really about time travel and this secret more than any of the other secrets in a game that bleeds secrets has held me, feverish, in its grasp.

The edge of the world

Eriko’s explanation of event science and Vrinda’s Tree goes into more detail than is appropriate or necessary here, as does the fictional research paper included with YU-NO’s Japanese strategy guide. In the inspection of either you will encounter such provocative expressions as “anti-photon coursing through imaginary space” or “intrinsic event spectrum of target events” or “ratio of causality propagation velocity to event viscosity,” so naturally it’s fun.

For our purposes it’s enough to elaborate only two more points.

1. Impending destruction

First, Eriko is on a deadline, and the timeline to arrest her criminal is the timeline of the world of Dela Grante itself. Dela Grante, Eriko explains, is caught in the whirl of a causal eddy: a sort of “causality loop” that occurs when a cause comes about thanks to an effect not prior to it but instead further down the event tree. In Eriko’s words it’s when “some cause along the flow of causality is born from an effect further downstream.” “Cause A creates B, and B in turn creates C. But now C creates cause A again,” she explains. The direction of time may be malleable without significant consequences, but modification to causal directionality can spell disaster, she tells Takuya. As it does in this case: caught in one such causal eddy, Dela Grante will soon be annihilated. Eriko must do her job before that happens.

2. The first event

Eriko’s explanation leaves a question burning in Takuya’s mind. He asks: if all that ever was or will be can be mapped onto a cause-and-effect tree, then from where does it all stem? What was the first cause and under the influence of what force did it instigate the chain reaction of cause and effect?

The answer is that nobody knows. The root of Vrinda’s Tree remains a mystery, even in Eriko’s world. For some, Eriko reflects wistfully, it’s the “domain of god.” For others, it represents “the furthest reaches of the universe, where everything began.”

“The beginning of the world?” Takuya wonders.

“Or the edge, if you will.”

The clock strikes 85 or so and YU-NO: The Girl that Chants Love at the Edge of the World has finished setting its stage.

Just in time for the climax.

The end of YU-NO

From here YU-NO hurtles toward its conclusion apace.

Takuya returns to the palace and reunites with his stepmother Ayumi. He demands answers. She entertains him with a story. Hundreds of thousands of years ago on Earth an ancient civilization foresaw its own demise. To avert extinction this country advanced in arcane arts warped itself into a dimensional void where it would remain as an ark to sustain its refugee populace until the end of the crisis. The jump saved the country and its people but consequenced a series of biological disasters by the conclusion of which the survivors had regressed technologically and had forgotten and mysticized their own history. To this day the drifting continent, Dela Grante, still orbits Earth from this separate dimension.

Every 400 years, Ayumi continues, occurs a calamity called the Wrath of Mother Nature. Takuya has heard of it: it’s the disaster that priestesses like Sayless and Yu-no have been charged with averting through ritual sacrifice. In truth this sacrifice does not appease the wrath of some mad god nor is it truly a religious rite at all but instead a procedure to correct a human error. Guided by the calculations of a supercomputer, Dela Grante’s dimensional orbit of Earth is not perfect, Ayumi explains. As it orbits Earth, it draws gradually closer. Every 400 years the two collide. The computer can stall the collision and save both worlds, but only if it synchronizes with a compatible host, a “priestess,” at the surrender of the host’s life.

There is another problem. On the 20th 400-year loop, collision becomes inevitable and Dela Grante materializes on Earth in the year 6,000 BC and crashes into the seaside that will one day become Takuya’s home. One of the main game’s primary timelines indeed revolves around exhuming the remnants of the seemingly pre-human civilization embedded literally into the bedrock of the town. Takuya recalls what Eriko told him, that Dela Grante is caught in a causal loop. Collision is inevitable. This time all Yu-no can do as the current priestess is minimize impact before she is either killed in the process or jettisoned by the computer into some distant dimension.

(Ayumi also enumerates here how she came to rule Dela Grante in only a matter of years and indeed how and why she and Takuya and Ryuuzouji arrived here in the first place, none of which is important to this post.)

But there is somehow an even bigger problem: they only have one day left.

Yu-no however faces her duty unflinchingly and after a standoff with Ryuuzouji in his true form she operates the computer that will save Takuya’s home while the attentive player realizes that she could not have done otherwise. The crash and its consequences are already inscribed in history. In a winding and roundabout way, the crash is what led Takuya here to begin with: the contact between Dela Grante and Earth, and the remnants of an ancient civilization that it left behind, is what spurred Koudai to immerse himself in the study of history. More importantly, you learn, it is what compelled him to leave Takuya and Ayumi behind to search the “wave of events” (as the game calls it) for Takuya’s birth mother, a Dela Grantian who became stranded on Earth and one day disappeared mysteriously. This was the ultimate purpose of his journey. So no collision, no Koudai. No Koudai, no letter. The rest is history, which is beginning to sound more and more, as Koudai wrote, like “an irreversible concept.”

Before Yu-no disappears, Takuya gives her one of the Jewels so that he might find his way back to her if they are lucky. Light engulfs him and when he blinks it out of his eyes the interface has reverted to that of the main game, with the mirror and the inventory and the Reflector and Jewels.

Takuya is back home in Japan and underground, trapped in a dark stone chamber with no escape.

The player understands the way out. YU-NO after all trains you in the art of escape, save and load, Game Over and continue. In a curious way that preempts Fumito Ueda, the game ends by reciprocating. You open the reflector map for the final time and find a Jewel stamped onto a familiar intersection, the night of Koudai’s letter. All the way back at the beginning. You didn’t place it but you know who did.

Takuya returns back to the beginning to find Yu-no. Reunited, they embrace. She describes how long she wandered across event space to arrive at this eventuality. He assures her that the two of them will be together forever from now on. The two travel backwards through causality, all the way back to the beginning, to “the end of the world,” where they encounter a sprout shimmering against the darkling void as it struggles through a crack.

They wonder what to name it. Yu-no decides. The game ends without telling you and if you assume that “Vrinda’s Tree” is the name then you do so with haste and without heed. The answer is hiding in plain sight. It’s in the game’s title: “Love.” YU-NO thereby centers this human emotion and feeling at the origin of and as the catalyst for all events. So named, the sprout grows before their eyes into a tall and sturdy tree under which they shelter. The End.

Narrative implications

If we understand the implications it’s because they punch us in the face harder than Sam punches Higgs.

If the root cause of all events is called “love,” then the game makes its point synecdochally, by means of parts and wholes. There is a trace of that first cause, it says, in every disparate event it grows into, and before it will let you see the whole, YU-NO spends a disproportionate, maybe even inordinate, amount of time showing you the parts that constitute it. However vague the concept, “love” is the catalyst for many of this story’s moving pieces. Koudai sets out on his journey out of his overwhelming desire to reunite with his first wife. Eriko carries out her duty as an interdimensional investigator in the memory of her deceased lover and research partner. In parts of the game that I did not previously detail, Takuya’s school friend Yuuki inadvertently hurts their mutual acquaintance Mio out of his unrequited love for her. Mio herself attends summer school alongside Yuuki and Takuya despite her good grades because of her admiration and indeed romantic love for Takuya. Takuya’s teacher Mitsuki pursues a sexual relationship with Takuya after Ryuuzouji dismisses her affections. Several of the game’s minor antagonists relentlessly pursue power out of love for it or for themselves. In hindsight it all sounds so soap-opera-ish that I almost have to laugh remembering how seriously I took it and how invested I was. But if the narrative threads that play out over the course of YU-NO’s “main game” tangle ultimately into melodrama, then it only proves the point. From the thoughts and emotions of the game’s characters stems a sprawling thatch of cause and effect of which Takuya is only one small part.

Nor are Takuya’s motives exempt. The conclusion of his journey is strange and maybe unsatisfying, the goal unfulfilled even as the credits roll. Even at the “root of all events,” Koudai remains out of reach. Takuya never manages to catch up with him. In place of Koudai himself is a fact that starts as a sprout and grows strong and firm with acceptance: that Takuya would never have made it here, would never have let the mystery of Koudai’s letter captivate him in the first place, unless he loved his father.

The experience of time

Of course there are other implications too — implications far more compelling and far less platitudinal than “everything we do we do for love.”

I’m being reductive, but so is the vomit sliding back down my throat.

I digress.

Back on track: YU-NO has far greater ambitions.

“The fundamental achievement of YU-NO is that it collapses the synchronous and diachronous layers of videogame time into a single narrative, that it blurs and often outright erases the line between narrative and metanarrative.”

Previously the Time Traveler’s Diary piece noted how YU-NO narratizes almost uncannily the concept of possibility space in video games. In thw quote above, it makes a similar observation, that YU-NO narratizes the experience of “videogame time,” which is nothing other than a superhuman or transhuman experience of time.

The game’s ending makes that clear enough. When it places love at the beginning of all events, tt proposes broadly that intrinsic to causality, a dimension surpassing time, are human thought and emotion — in other words the experience of being human. The experience of being human, says YU-NO, is an experience superordinate to time.

In reality this is not true. We live beholden to time and have no way to escape its passage. We can’t control our travel through time, forward or back.

But in a video game, on the other hand, it is possible to manipulate time, to travel backwards and forwards and sideways, and not only is it possible: it’s mundane. “Time in videogames is idiosyncratic,” the same piece writes. “It jumps forward and skips backward, branching and looping at will. You die and repeat a stage. You win and replay on hard mode. You reset, over and over, perfecting a run. You use a password to read ahead to your last save. All of this is considered normal, natural.”

In fact the ability to surpass the human experience of time is the greatest trick a video game has up its sleeve to empower its players and, as an acquaintance pointed out to me not long ago, to instill confidence. Utterly unthinkable in reality, in a video game you can keep trying until you succeed by returning to a point before you failed.

The paradigm derives from a monetization model, one of the oldest by which video games have operated: in the arcades, you can warp time with godlike ability as long as you keep dropping quarters in the machine. You play the game until you fail, at which point the game penalizes you with death. To undo your death, to go back in time and try again, you pay a fee. There are no continues in life, but in a game you can transcend temporal limits and keep doing so as long as you have change to spare. The cost associated with play that continues from failure is a charge to reverse and overcome the normal human experience of time.

Today many games repurpose this monetization model via electronic microtransactions: pay now to continue immediately, or don’t pay and wait. Pay and surpass the human experience of time, or don’t pay and remain accountable to it.

More traditional console and PC games however remain detached from this economic model in favor of a different one that enables a temporal transcendence even more complete. Payment comes upfront and death becomes an opportunity at no cost: when you lose, you get to try again without paying, without penalty. And not only without penalty, but with the valuable reward of foresight. Suddenly you can save a game, load it, overwrite it, or keep it in your back pocket for later. Or you can sequence break, circumvent the rules to twist time in your favor.

Released for computers and consoles, YU-NO is of course one such game.

Earlier I wrote that YU-NO is not really about time. This was a lie. YU-NO is about time. Specifically it is, like thousands upon thousands of other video games, about overcoming and trivializing it. YU-NO is simply a game that by accident or otherwise (I don’t presume to know nor does it matter) recognizes that playing a video game is an act in transcending the normal human perception of time.

In a sideways, 89-hour-seven-minute-25-second way, YU-NO argues with mathematical testimony for the triviality of time. In hindsight it should have been obvious, even on a purely ludic level, if only because nothing happens in YU-NO until you make it happen. Time doesn’t move forward until you do. There are no real-time elements and nothing about the game’s world changes until you make a choice. Everything depends on you. The whole world is at the mercy of your mouse click. In the face of this sovereign instantiator, time means nothing. If things stop for a while and the whole world seems to pause, well, maybe God has a hand down His pants.

According to the rules of the game, effecting change requires human action and has nothing to do with time.

That YU-NO proposes the triviality of time narratively is even more obvious. Its entire premise involves rendering time increasingly inconsequential by obtaining Jewels that one by one not only empower you to transcend time but lead you ultimately to the discovery of a force more powerful than time. The barest description of this game is that it follows the trajectory of a main character who becomes aware of, and ultimately comes to inhabit, a dimension that supercedes time.

There is something more powerful than, more valuable than, time. We may even recognize the expression of the concept outside the confines of the game’s story or its rules, in the very act of its play. For the player who spent 100 hours and turned the game off one final time enriched, the expense of time means less than the extracted experience.

I’m one such player, obviously so here is my thought. If YU-NO is, as has been claimed, “meta,” it’s not because it indulges in videogame stylistics already fossilized by its 1996 arrival — in FM synth and in demo reels and in the motif of inserting coins to continue, reiterated to the point of exhaustion. (What you’re inserting them into is slots in stone walls steeped in darkness and what you’re inserting them to continue is your path through a lost evil death maze deep in the ancient belly of the earth, but still.)

Rather it’s because YU-NO narratizes the exact transcendence of time that inheres in videogame play and in so doing YU-NO celebrates narratively and openly what video games as a genre and form of art celebrate through the act of play, unspoken and undercover: achievement transcending the limits of time.

YU-NO therefore is not only a masterpiece of the artform but also a guidepost to its understanding.

Further, YU-NO serves as an avenue towards a codified articulation of Kojima’s style of and approach to game design — because it represents the exact opposite of it.

Metal Gear Solid 2

Once derided heavily for deviating in subject matter and tone from its predecessor, Metal Gear Solid 2 currently enjoys widespread acclaim for the same.

In some ways, however, the modern appreciation of the game stems from a misapprehension: thematically the sequel does not stray particularly far from its predecessor.

At the end of Metal Gear Solid’s story, its main character, Snake, must reckon with his impending death. At Naomi’s behest, he decides to embrace what little lease on life he has left. Even if clumsily (primarily because Naomi was the one who wrote Snake’s death sentence to begin with), the story concludes when the main character can come to terms with death, with his own mortality, and still believe that life is worthwhile.

In this way Metal Gear Solid 2 does not deviate thematically from Metal Gear Solid but continues from it to recognize broader implications: reckoning with mortality, the sequel identifies, means accepting that you are beholden to the passage of time, which is the conflict at the center of the game.

The villains of Metal Gear Solid 2, the Patriots (later recontextualized but in this game a secret society that has controlled the United States government from the shadows), will not accept a world poised thanks to the proliferation of advanced communications technology to move on from their supervision of culture. To prevent their obsolescence at the hands of the clock, they create AIs to maintain the same control over society that they have always enjoyed irrespective of the passage of time.

Our character meanwhile not only fights unwittingly for their cause but also operates secretly with the same attitude.

“Do you know why we chose you […] ?” the AI version of Colonel Campbell asks Raiden at the end of the story. “It was because you were the only one who refused to acknowledge the past.”

At the same time, Raiden refuses to look to the future, has forgotten “what day tomorrow is.”

Raiden is the perfect candidate for this experiment to use AI to overcome the confines of time because he won’t acknowledge his past or face his future: for him, time has no meaning.

That the emotional climax of the game involves a reconciliation with time is therefore no surprise. Thirtieth of April — the date whose significance Raiden has been trying to recall — is the anniversary of the day he met Rose. Just in time, he remembers that the future, after all, was nothing more or less than a commemoration of the past, reconstituting his own temporality in the process. Raiden’s epiphany in this second MGS game is an extrapolation from Snake’s in the first: that we are living at the mercy of time, and that there is value in doing so.

The game communicates the magnitude of the sentiment symbolically. Though the Patriots long for a functional immortality, imagery of death, such as skulls, characterizes the AIs that result from their ambition.

Raiden and Rose on the other hand will have a child, leaving behind a trace that — like all traces, genetic or otherwise, Snake explains at the end — depends on their own impermanence.

Narratively, then, Metal Gear Solid 2 counteracts the experience of atemporality that inheres in the play of video games, the experience that YU-NO makes plain through its story. The story of MGS2 instead extols the human experience of time and of living inside of its confines and even the inevitability of death.

Contradiction

Metal Gear Solid 2’s gameplay on the other hand tells a very different story, one that in fact contradicts the game’s narrative. Ludically Metal Gear Solid 2 is a tightrope of arcade stealth strung taught above a Game Over trampoline. Its simulated reality hangs in the balance. One false move and you can kiss the human experience of time goodbye as you bounce right back with a continue. Save games, VR missions, dog tag records, Snake Tales (we could without deviating from the topic detail External Gazer; we would be here all day) — all of these reveal what Metal Gear Solid 2’s narrative components seek to hide. Despite the game’s narrative ambitions to contradict the fundamental atemporal character of videogame play, this game, like most others, is still concerned intimately with overcoming human temporal limitations through the concept of Game Over and continue, which means dying and then returning to a point prior to death.

Game Over

For how long Kojima’s games continued to preoccupy themselves like MGS2 with attempting to sanctify the human perception of time is impossible to discern because they haven’t finished doing it yet. Probably they never will. Nobody really has more than one story to tell after all, and if they tell it again it’s to tell it more plainly, and if they keep telling it after that they will probably keep on telling it until it fits on a napkin. Kojima’s is about rectifying an error of time. Metal Gear Solid 4 depicts a world whose time appears to be moving in reverse and whose main character impends towards a premature death and will not end until it rights the former and corrects the latter. MGSV wears its fixation on its sleeve as its main character and player alike awaken into a world of cycles and repetition, where time makes no sense and its passage seems to have lost all meaning. In Death Stranding the wide-scale distortion of time and its eventual rectification are the sleeve.

Some start with the napkin, knowing exactly what to say and how to say it and in how many words. Ueda is one of them. He wrote Ico on the front and because there was enough room wrote Shadow of the Colossus on the back and could have stopped there and very nearly did.

Kojima is not like Ueda. He took the long way around. To whatever degree the Metal Gear series exalted the human perception of time against the atemporal character of its medium, it never unshackled itself from the infraction of the Game Over screen, from continues and exits and save games and retries, from the distortion of time that empowers us to play. Mission Failed. Game Over. Snake is Dead. Yet even as it contradicts the narrative aims of the series, the Game Over concept is one to which Kojima and his team have never failed to call attention. Playful and strange, Metal Gear’s Game Over screens form some of the series’ foremost audiovisual iconography. They make an aesthetic impact, play with the player, recall one another, and if in so doing these moments that serve to break a game’s continuity instead become emblems that preserve it, then Death Stranding is the version that fits on the napkin.

Waiting game

Redesigning the Open World to Change the Future is an astute analysis of Death Stranding by my acquaintance and, if I can say so, friend on twitter Light01C, whose passion for and knowledge of video games I admire immensely. I thank him again for writing this piece and for taking the time to create an English translation of the original French.

The analysis discerns cleverly that one of the primary projects of Death Stranding is to divest itself from the Game Over concept that depends on a game avatar’s death and originates in the monetization model of the arcades. (My application of this monetization model to my own understanding of YU-NO above actually stems from here.)

“Failure in the game,” the piece explains, referring to Death Stranding, “shifts from dying as an avatar to not completing your delivery.”

What the piece recognizes, that Death Stranding “focuses [more] on the packages and less on the avatar,” forms the core of one of Death Stranding’s peculiarities: that the life of the main character hardly matters.

Like Ico before it, Death Stranding deprioritizes the life and safety of its main character. Sam’s life is unimportant and the impact of his death is minimized. Ico achieved this effect by crafting rules and mechanics that subordinate Ico’s (the player’s) safety to Yorda’s (an AI’s), but Death Stranding does the same by transforming Game Over into a diegetic concept. A “repatriate,” Sam has been rejected by death and keeps coming back to life, a walking checkpoint. Upon death, he returns to life without penalty, save for perhaps some mild nausea, close to where he died. The experience is entirely contiguous, uninterrupted by a menu or the need to restart from a previous point. There is a form of Game Over screen (“Order Failed,” it reads) associated with Sam’s death, and indeed it necessitates a restart, but it’s rare and highly conditional and you may not see it even after hundreds of hours of play. Instead, Death Stranding largely treats the entire idea of Game Over like a vestigial organ. To give it new purpose, it transplants it out of play and into narrative, a gameoverectomy. Returning to life after death sheds the nature of a conceit to serve the rules of a game or to preserve the integrity of a virtual world and instead becomes an experience intelligible to the avatar himself.

The avatar himself: Sam is also a deliveryman. Like Ico, his goal is to keep his charge safe. He ferries the packages for delivery to waypoints that dot the game’s open map, keeping the goods intact. The safe delivery of packages rewards him and the player with high mission rankings and more likes (Death Stranding’s version of XP). Destruction or misplacement of the packages, on the other hand, mean that Sam has failed. As in the case of Sam’s death, failure to complete an order does not provoke a Game Over screen in most cases. Typically all it does is force you to redeploy the packages or undertake the order from its inception, possible only after a certain number of real-world hours. In this way, Death Stranding follows a blueprint so simple and elegant that it leaves intact the serendipity of a genius accident. Failure does not afford the player the ability to retry instantly, the power to bypass the normal human experience of time. It does the exact opposite: it forces you to acknowledge your subjugation to time. Failure makes you wait.

(You can still load a prior save manually, of course, but the game never outright suggests this behavior as overtly as a Game Over screen might and in fact discourages it in a couple different ways.)

Reneging on such a time-honored concept as “Game Over→Continue”, Death Stranding, the Redesigning the Open World piece explains, “propose[s] new standards against the immutable codes inherited from arcade games.” It turns death into a diegetic experience that proceeds unbroken for both the character and the player without distorting time. And it declines to reward failure with the power to overcome temporal confines, instead panelizing it via an enforced refractory period.

Antigame

In this way, Death Stranding follows the trajectory of the Metal Gear series and goes further.

Like Metal Gear, it exalts the human perception of time through its story. It does this so overtly, so blatantly obviously, that I feel no need to detail its methods here. It’s enough to point out that the game’s story ends in exactly the same way as Metal Gear Solid 2’s, with the recovery of the normal human perception of time. It’s just a little less abstract about it:

Unlike Metal Gear, however, Death Stranding is able to communicate the idea through its play as well by largely eliminating the player’s capacity to break free of the confines of time. Almost all that you accomplish in Death Stranding you accomplish from inside the limits of time. If YU-NO exactly narratizes the inherent atemporality of video game play, then Death Stranding is its diametric opposite. In YU-NO, as in so many games, time means nothing. In Death Stranding, time means everything. So maybe for all its overt “gaminess,” Death Stranding is something of an “anti video game”: a game whose narrative calculates worth beyond measure in the confines of temporality and whose play celebrates achievement from inside of, and in the face of, the limitations of time.

Kojimaesque

Over a year ago on this blog I suggested a sort of project to articulate what I and probably others call the “Kojimaesque,” the undeniable but strangely indefinable quality of Kojima’s games that sets them apart. The basic question at the heart of the endeavor was: if Hideo Kojima is one of a handful of video game “auteurs,” then what is it about his games that make them distinct?

I’m not the first one to ask this question nor will I be the last. Platonic Solids, Solid Snake: Hideo Kojima’s Erotic Formalism is an article that I keep coming back to because at its core it’s trying to answer the same question (and because the writer’s blatant attachment to jargony, elliptical prose breeds a begrudging, lip-biting camaraderie in me, even if they employ it less artlessly and with more restraint than is my proclivity).

Anyway, it’s taken a year, but I believe YU-NO and Death Stranding have elucidated at least a little bit of what the Kojimaesque entails.

To recap:

YU-NO captures a quality that inheres in so many video games that it can be said to characterize the entire art form. That fundamental quality is the triviality of time. The narrative and play of YU-NO center on achievement unfettered by the human experience and perception of time.

Death Stranding countermands on every level this fundamental quality of video games. The emotional climax of its story results in a restoration of the normal passage of time and its play makes every effort to subject the player to temporal restraints. Contrary to its video game lineage, Death Stranding therefore celebrates achievement inside the limitations of time.

The two are opposites then, conveying contrasting messages through the medium of video games. But if as video games these objects of analysis are mathematical in nature, then I won’t hesitate to apply mathematical principles to extrapolate a simpler model by which to understand. So let’s cancel out one of the common terms of the equation to see more plainly what it really means:

In the spirit of the video game medium, YU-NO focuses on achievements that transcend limitations.

On the other hand, Death Stranding, contrary to that spirit, celebrates achievement in the face of limitation.

Achievement in the face of limitation: I contend that this value characterizes the entire Hideo Kojima body of work and that it is a foundational component of the Kojimaesque.

GDC 2009

A few months ago I watched a video entitled Renga: A Document of Hideo Kojima. The above is a reupload. The original was removed when the creators decided to delete their channel, which I believe happened sometime in mid-2021. With the deletion of the channel we sadly lost a handful of other documentary-style videos centering on Kojima games.

One of these videos I recall well. It was about Kojima’s keynote presentation at Game Developers Conference (GDC) 2009. The video claimed that this keynote presentation was the only time Kojima ever truly explained his philosophy of game development.

Hyperbole, right? It had to be. Curious, I watched the presentation. It’s on youtube:

It has taken me almost two years to recognize, but the creators of the Renga video were absolutely right. If you want to understand Kojima’s style, and by extension KJP’s (new and old), this video is absolutely essential.

It’s Hideo Kojima’s most important “interview,” bar none.

In just under an hour and a half he succinctly describes the trajectory of his career in the gaming industry and how he navigated around the barriers that impeded him. Out of the contours of his journey we may extrapolate the defining feature of the Kojimaesque, refine a career into a philosophical approach.

He explains by metaphor. We don’t have to envision the wall; it’s right there for us to see, on the screen, the “wall of impossibility.” But Kojima did have to envision it, and more than that: he had to overcome it. The year was 1987, and the platform — unfortunately for young Kojima, who fell down the rabbit hole that led him to Konami in the arcades, and later on the Famicom — was MSX2.

If you’re reading this, you already know the story. The theme: military. The genre: action. The mission: impossible. The SCC wasn’t even out yet, for god’s sake. This thing wasn’t even going to sound good. (The first Konami cartridge to implement the company’s famous Sound Creative Chip was Gradius 2, product code RC751. Metal Gear was RC750.)

Kojima’s career — personified by Snake in the presentation — had hit a wall. Unlike Mario, it had no way of jumping over, no means to surmount the barrier, no chance of attacking the problem head on. Snake’s only option in the presentation — and Kojima’s only option in real life — was to go around. To use his own ingenuity, the support of his mentors, and the tools at his disposal to avoid the obstacle entirely.

So, as he says in the presentation, he changed the mission. Instead of creating a game to match Capcom’s Commando or the other high-octane war-themed games of the era (to match Konami’s own Green Beret, perhaps), Kojima would create a game themed around a stealth mission. “If you’re reading this, you already know the story.” The people in the audience that day probably knew the story too. But what they didn’t know, what Kojima explained only once, here, and never again, what I took almost two years to understand, and what the creators of Renga got that no one else did — is what it meant.

And what it still means: that the process of confronting an insurmountable barrier and finding a way around it, of coming up against your limitations and achieving not by overcoming them outright but by understanding and avoiding them, doesn’t just describe Kojima’s career. It characterizes his games.

Kojima continues. After the successful release of Metal Gear came Metal Gear 2. Then Metal Gear Solid, Metal Gear Solid 2, and so on. For Kojima and his team, each arrived with its own set of problems to solve, its own “wall of impossibility” to overcome. And every step of the way, they dealt with roadblocks not by facing them head on but by using their wits to navigate around them entirely. Mario, Kojima shows in the presentation, can leap over any obstacle, trivialize any impasse like it’s nothing. With enough speed and the right jump, there’s no wall he can’t overcome, no gap he can’t cross. But Snake is playing by different rules: he can only run so fast, he can’t jump at all, and the obstacles have guns. Charge in headlong, and it’s Game Over. Snake’s strength, then, is nothing more or less than the strength of Kojima and his team: to win not by overcoming limitations but by recognizing them and making a path around them.

If you can’t enter through the cargo door, sneak in through the ducts. If you can’t make Commando on the MSX2, make Metal Gear. If you can’t handle the challenge head on, then don’t fight a losing battle. Instead achieve your goal in the face of limitations by turning your shortcomings into your aesthetic. This approach characterizes not just the trajectory of Kojima’s career as a game designer but also the gameplay of the Metal Gear series.

The long way around

On an early winter night, a restless question tore at the edges of my insomniac mind. When someday we are able to chart all the unobservable matter in the universe into nodes of light then we will have in four perfect dimensions modeled the true shape of the human soul. So maybe if I could see the stars, they would map my answer onto the sky. But human ingenuity has found a way to pollute even light, and considering I was close enough to hear an excited highway at — Jesus, I don’t even want to know what time it is, roll over — you can very well imagine that if I was looking for an atlas, the splotches mottling the ceiling would have to do, peculiar in shape and suspicious in origin and not much, not much at all, to rely on.

Death Stranding is possibly the most astounding video game ever conceived, in every sense of the word. It is a nightmare of a paradox. It is a photorealistic cartoon. It is an arcade score-attack mission set in a modern open world. Most of all, it is a game of limitations that arrived at a time when the possibilities of a video game were more than ever before unbound of constraints and contained by imagination, budget, and skill alone.

The Metal Gear series under Kojima turned limitation into a design principle, weakness into style. But if style is substance (it is the only substance), then Death Stranding’s drops all pretense and facade.

A mirror of Super Mario Bros., Death Stranding is all about trading the speed and power to overcome obstacles for the patience and vision to navigate around them and make a path for yourself against your limitations. Mario runs from left to right, but Sam must travel the opposite way, from right to left, recharting the path of American expansion from east to west. His journey will be slow. It will take time. Unlike Mario he can’t run and jump over every gap or wall that blocks his way. At first, his quest will seem hopeless, the barrier of impossibility too high to surpass. Every step is just one more chance to stumble and fall. The destination isn’t much more than a nice idea.

But unlike Mario, he has time. In time, Sam will circumnavigate these obstacles, chart a path around them, scanning the way forward to avoid the danger zones and using tools for safety. In more time, and with the help of his fellow porters, his otherworld counterparts on the same journey, the paths he walks will become trails. In even more time, and with enough dedication, the trails will become roads, and these roads will take him around all the obstacles that stand in his way, barrier and chasm and MULE camp alike. Even mountains.

Slowly but surely he will reach his goal, and the time will come to travel back east, to retrace his steps. When this time comes and he looks back, he will realize that he has overcome the barrier that at first seemed so impossible to surmount, a steep hill or a swift stream maybe, and many more barriers along the way.

Then and only then will he be able to run back (west to east, left to right) like Mario.

At a time when hardware limitations the likes of which Kojima and co. faced in the 80s are a distant memory, Death Stranding nonetheless takes its players on a journey whose rules render barreling straight to the finish line even more impossible than did Metal Gear’s, an elliptical, roundabout journey that isn’t straightforward and that takes time.

Death Stranding insists on the worth of a restricted, human experience of time, but this is only a microcosm of its broader aims, and in this way it extrapolates from the conclusions of MGS2 in the same way MGS2 extrapolated from the conclusions of MGS1. Death Stranding identifies that the importance, the very meaning, of achievement hinges on the fact of limitation.

Finally I slept, dreamless, for 15 hours. When I awoke, I understood something. That all I have ever had is time. Death Stranding is possibly the most astounding video game ever conceived, in every sense of the word. If through its design it proposes the worth of the 30-year process that culminated in its creation, then it is its own proof.

By Kiyan.