In the Japanese game industry there is a trend, which has existed for decades (since the 70s or early 80s I guess), of creating a new genre for every game. Though these are more like a tagline or marketing copy. Basically just a quick and unique descriptor created to describe a general feeling or vibe the game is meant to impart, or to quickly deliver some of the keywords of the game’s design.

For the Metal Gear Series it’s “Tactical Espionage Action,” or “Tactical Espionage Operations” for Peace Walker and MGSV. The series also used a couple other of these “genre taglines,” such as Metal Gear 2’s “Tactical Espionage Game,” or “Tactical Roleplaying Adventure Game” for Metal Gear.

(via Moby Games and Gamefaqs)

For Kojima and Kojima-adjacent games outside of Metal Gear, “High Speed Robot Action” is the well-known label used for Zone of the Enders, and it is indeed shown on the back of the Japanese case for the PS2 version of Anubis. The first one was labeled “Robot Animation Simulator” in the same spot, though I think the “high speed” line was also used for ZoE1 elsewhere (could be wrong about that).

(via Moby Games and Moby Games)

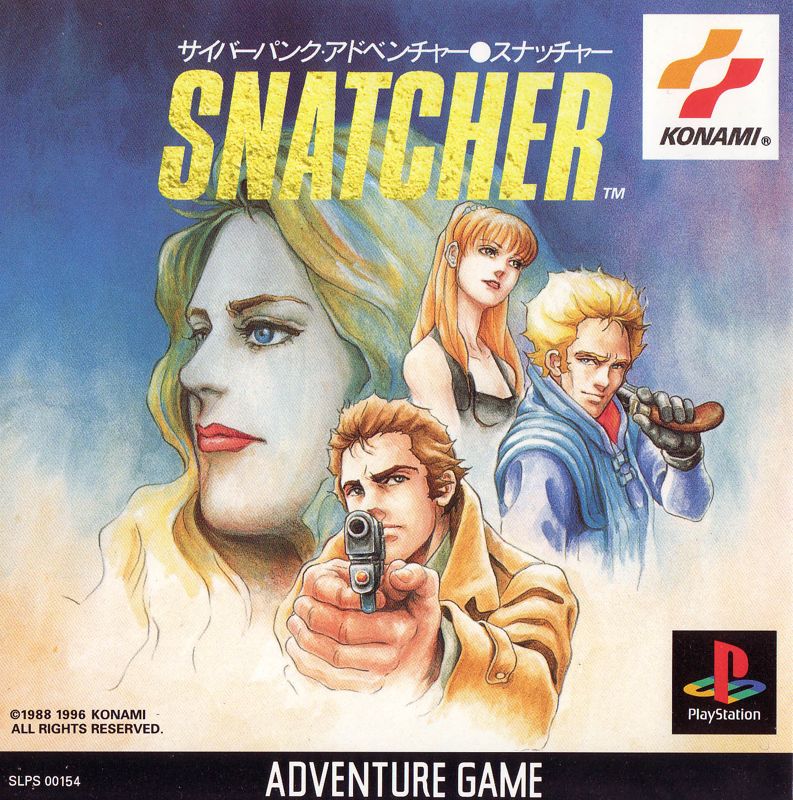

Snatcher was called a “Cyberpunk Adventure,” which I would assume made the game sound sort of cutting-edge and cool. On the PS1, most (all?) Konami games had a strip at the bottom of the cover with the genre labeled, and these were usually more general from what I’ve seen, more in line with the Anglosphere understanding of genre as being more fixed. Snatcher’s PS1 version simply called it an “Adventure Game,” though retained the “Cyberpunk Adventure” tagline at the top.

(via Moby Games)

Some other examples outside the realm of Kojima and KojiPro include “Super Bio Cyber Shooting” (Aleste), チーム連係型ハイスピードハンティング (God Eater, means something like “teamwork-based high-speed hunting,” forgive my weak Japanese), “Survival Horror” (Resident Evil series).

“Survival Horror” is an interesting case since it now sees widespread use outside of the Resident Evil series, and is even sometimes applied retroactively to games that predate the first Resident Evil, like Alone in the Dark (which influenced Resident Evil) or Capcom’s Sweet Home. I think the Anglosphere understanding of genre in video games is more fixed. And it may be more prescriptive because of that. And certainly it is less descriptive, with broader, less-nuanced categories like “action,” “platformer,” “life sim,” etc. Nevertheless, certain of these “genre taglines” used in Japan have permeated the English-speakig videogame world.

Of course the Japanese industry has this way of thinking too, with codified abbreviations like “ADV,” “ACT,” “STG,” “FTG,” etc — just appended with more specific phrases for marketing, which often can provide a deeper insight into the intention of the game’s design.

Another genre adopted into the English videogame lexicon is “visual novel.” This one is a little misleading I think, and problematic. The problem being that the way it’s used in English encompasses a far wider range of games that the phrase was created to describe. It was created by the highly influential Japanese developer Leaf for their series of novel-style games including Shizuku and Kizuato. The design and genre name of these originated from Chunsoft’s “sound novel” series (Otogirisou, Kamaitachi no Yoru, etc.), which inspired an enormous quantity of Japanese novel-style games, Leaf’s included. System Sacom’s Novel Ware label/denomination has also been identified as an earlier, related style of game.

(via Moby Games and twitter/x)

As a side note, did System Sacom’s Novel Ware line influence Chunsoft’s sound novel series? I haven’t seen any information confirming or denying the idea, but I would probably have to look in Japanese, which I am hesitant to do since I can hardly read the language at a satisfactory level at all. To the question, in 2018 Koichi Nakamura stated that he originally envisioned Otogirisou as a game that could be appreciated by those who are unfamiliar with or who do not understand the appeal of games. He said:

“I was dating a girl at the time, so I showed her Dragon Quest and said, ‘I made this thing everybody’s talking about. I was involved in making it! Isn’t that great?’ But she wasn’t a gamer, so she tried getting into it and said, ‘I don’t really get what you’re supposed to do. I don’t get what is fun about this.’

“So I started to think, ‘Well, maybe I need to make a game for people who haven’t played games before. An opportunity for somebody to get a controller in their hands and become acclimated to video games.’ I thought about the old text adventure games that I’d played and realized they’re pretty simple. But even then, they require a bit of knowledge about games. If a game is command-based, you as a player have to control the game and tell your characters to do things. Even that’s a bit complicated.

“I thought that maybe I could even simplify it further by having it be decision-based, where you’re just reading the story and it will come to a branching point where it’ll give you a choice: The character does A, B, or C. It’s very simple, but it also gives the player some level of interaction with the game. I figured something very simple like this would be something anybody could pick up, and maybe it would also lead them to playing other games in the future.”

So he identifies that as the impetus for the concept.

Anyway, back on topic, the term proper (“visual novel”) was created to describe games that told a story in prose, like a novel. Its usage today, however, in English at least, is more broad, and usually encompasses the entire history of Japanese adventure games, applied retroactively to games like Portopia Renzoku Satsujin Jiken or EVE Burst Error (for example). Games that were never intended to be highly novelistic, even if they aspired to more intricate narratives and narrative design than most of their contemporaries. Sometimes the term even applied to other types of games as well. Just look at the English-language “Visual Novel Database.” While an admirable database, the site is laughable with regard to its inclusion criteria. For instance the site often labels even non-novel-style games as “visual novels” for some reason. (NSFW link →) Dungeon-based RPG Dragon Knight has an entry on the site for instance, as does even Tokimeki Memorial. And that’s just two examples. While I appreciate the information it catalogues, the site is packed with games that probably should not be on there. I find the usage of “visual novel” to be problematic when applied retroactively like this, because it can obfuscate the intention and lineage of the design of the games to which it is erroneously applied.

(via Moby Games and Gamefaqs)

Policenauts is a good example. Often it’s called a “visual novel” today. But this is a rather poor descriptor. As Project Itoh noted decades ago on his site, Policenauts, unlike many Japanese-style adventure games produced later, avoids description in favor of dialogue to the extent possible. Itoh notes that this decision to favor dialogue contributes to the game’s movie-like style. Assigning the game a label like “visual novel” rather misses the mark then, since the game is not really novelistic in effect. Nor is it novelistic in its intention: its “multi-process scenario” system was meant to build a truly interactive game world inside the context of a linear detective mystery story despite the absence of branching narrative or progression-gating puzzles (for the most part, that is; there are obviously a few minigames such as the infamous bomb section). In fact, Konami labeled the game “interactive cinema.” This term is displayed prominently on the front cover of the PS1 version, but it also appears on the back of the box for the original PC-9821 DOS version of the game. I think this is a more accurate descriptor that better captures the “multi-process scenario” system used in the game.

Though Itoh refrains from describing Policenauts as a “visual novel,” ironically he did use the term “visual novel” (ビジュアルノベル) in relation to the game when he wrote a column for Konami. It’s been said that the term “visual novel” is not used in Japanese to refer to domestic adventure games, or at least wasn’t until recently (last 5 years or so). However, this is not totally correct. It may be the case that it was just uncommon to apply the term in this way.

Another genre name that is a little suspect is “metroidvania.” This one is also retroactively applied sometimes, I think. My problem with this one is mostly the same, that it mystifies the actual intention and influences of a game’s design and concept when applied retroactively, and can suggest an ahistorical understanding. Further, even more than “visual novel,” “metroidvania” may represent a detriment when thinking about designing one’s own game. Subscribing to the idea that there is a shared history between and a common thesis to the design of Metroid games and the design of Castlevania games could negatively affect game development (i.e. could confuse the core design of a game) given that the term originates from perfunctory similarities between the two series recognized after the fact. It doesn’t seem accurate to me in any case. I guess my thoughts on the matter aren’t really too developed. More to think about in the future…

Finally, I think it would be pretty funny if, like Resident Evil’s “Survival Horror” tagline, Metal Gear Solid’s “Tactical Espionage Action” had caught on and became a broader and codified genre internationally. (Of course the phrase was retained internationally, but just as a tagline for the game, similar to how it was used domestically.) These days there are handfuls of smaller-scale games that aim to recapture the design and aesthetic of Resident Evil and its many contemporary imitators. If “Tactical Espionage Action” caught on like “Survival Horror” did, would we currently be seeing a rise in MGS1-inspired games?

Well, probably not. After all, Resident Evil inspired many more direct imitators in its time, to an extent that MGS1 never did. Even Konami made their own, that being Silent Hill. Still, it’s a fun what-if scenario to think about.