Been playing a handful of adventure games lately. One of them is Clannad, which I surprisingly never played until now. Though I dropped it cause it was immensely boring. Though I do have some stuff to say about it and I might do a separate post on it to articulate what about it I thought was interesting and why I still didn’t like it in the end.

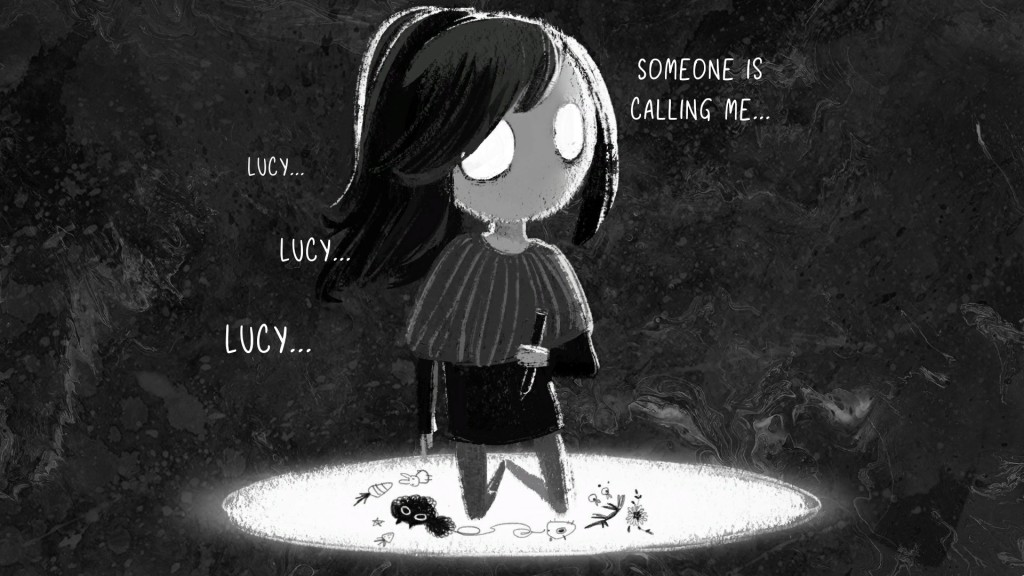

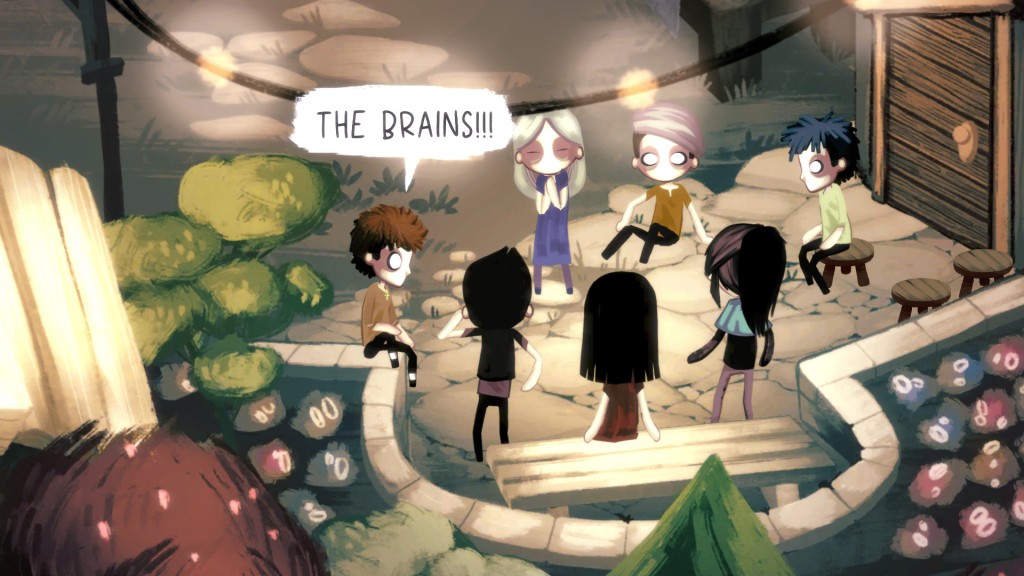

Another one has been Children of Silentown. This one is fairly new as it came out in early 2023, and it’s published by Daedalic. Sadly Daedalic has exited the game development business after the Lord of the Rings: Gollum fiasco, and that’s a shame since I’ve truly enjoyed a lot of their games over the years.

Anyway, they still publish games and Children of Silentown is one of them. Children of Silentown actually closely resembles the type of game Daedalic themselves used to make. It’s a point-and-click adventure game with inventory-based puzzles, similar to the classics of the genre. Something interesting with point-and-click games nowadays is that they can be played with a controller. And that’s how I’m playing Children of Silentown. So technically, for me and anyone else who uses a pad, the “point-and-click” moniker is not really accurate, but used more to describe the design of the game and where it’s coming from.

Controller support is the standard for basically all modern games. I don’t want to ruminate on it too much here, but the convergence of game platforms, hardware, and technologies is leading to interesting changes in the business and design of video games, changes whose trajectories we are currently witnessing play out. Like, for example, how a style of game design (and entire genre) defined by and ideated around the specifications and limitations of a specific play environment (mouse-equipped PCs) persists well beyond the point where that limitation has been surpassed.

As limitations continue to be trivialized and hardware homogenized, what technological limits will game design be able to play at, and to test? I don’t know the answer to that. I wonder how things will play out. It’s my opinion that game design won’t meaningfully evolve without meaningful limitations. Today limitations are often a matter of resources, skill, and experience rather than being technological in nature.

Anyway, Children of Silentown. The gameplay is classic and loveable, even if the scenarios are a little bland. One thing I find mildly irritating in adventure games is when progression is gated by trivial problems. One of the reasons I admire YU-NO so much and consider it to be my favorite video game is that the puzzles feel greatly consequential to the game’s narrative. Children of Silentown’s puzzles certainly provide insight into the personalities of and relationships between characters, as well as information about the overall mystery, but can feel a bit arbitrary. Still, I enjoy the (mostly) sensical lateral thinking they require to solve.

Story wise, the game seems to be building towards a thesis regarding the value — as well as danger — of self-assertion in a society where silent conformity and adherence to social hierarchies is enforced. Those who speak too loudly are disappeared into the mysterious woods surrounding the town. The town members encourage silence. Meanwhile, as the player conducts their investigation into the disappearances, they come to realize that the outliers of the town, such as the bullied Silver and outcast Blue, hold key information needed to solve the mystery. The unaccepted and the nonconformists are actually the most important people and also those who come to the most harm.

Anyway I haven’t finished the game yet so who knows.

Back on the design topic, there are a few moments in the game that I would consider to have Japanese adventure game style design, interestingly, though the game is European (dev/pub). At least one section of the game has been a “talk to everyone in the area to proceed” section with no real puzzle to solve — this is classic Japanese ADV design where progression is just a matter of talking to everyone/going everywhere/clicking on everything/choosing every option until you trip some arbitrary flag and the next event happens, with no real logic or reasoning involved. This is a blatantly unfun game system, and there’s a reason why Japanese adventure games moved towards the “visual novel” style that just cuts the fat and only lets you interact at prescribed junctures where interaction is meaningful.

Children of Silentown also frequently adopts the Japanese approach of gating progression behind distinctly embedded puzzles rather than narrative-based puzzles. What I mean by this is that while most of the game’s puzzles require the player to think about which item or ability to use to solve the problems the game world and characters present them with, others are just a sort of brain-teaserish minigame with its own rules, disconnected from the narrative (or connected only on a thematic level). This is Japanese-style adventure game design, which reduces narrative-based puzzles and replaces them (if at all) with minigames focused on internal rules. Think the bomb section of Policenauts.

Currently and historically Japanese game design values rules, roteness, prescriptivity, clarity, and orderliness, explaining why Japanese game creators can develop action game systems at a level unmatched by the rest of world, yet struggle to create compelling adventure and RPG design. (Actually “struggle” is the wrong word, since they mostly don’t even try, to their credit.) Children of Silentown, while obviously not Japanese, partially approaches adventure game design with this mindset.

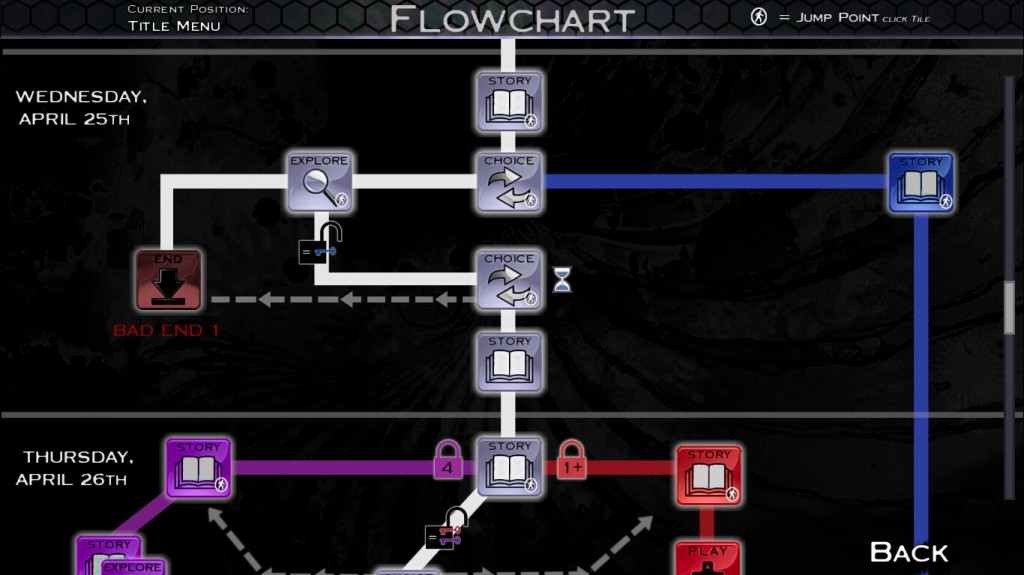

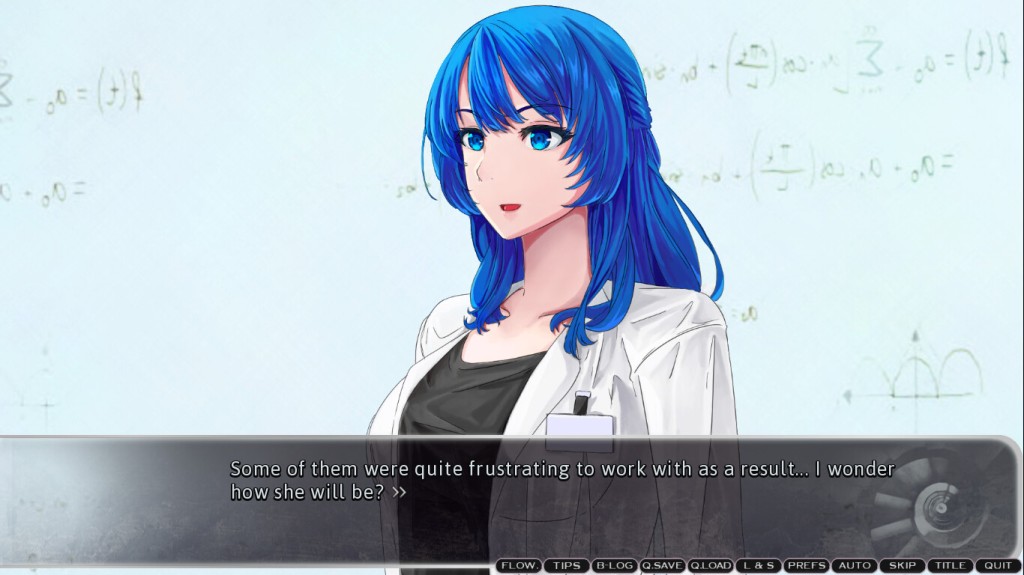

Speaking of Japanese-style design, another adventure game I recently completed is Synesthesia. Like Children of Silentown, this is a recent game (released in 2023) and adopts a Japanese approach to its adventure game design, though much more blatantly than Children of Silentown. It was also surprisingly awesome. I really liked it, a lot more than I thought I would. It’s basically like a much more succinct version of an Infinity series or Science Adventure series title, and, to its credit, it’s able to build compelling characters, an intriguing sci-fi backdrop, and a cool mystery to solve in a much shorter space than any of its obvious influences do. In a sense it actually surpasses its influences in some ways.

It’s an economical approach to this type of game, and kind of reminds me of Kanno’s work pre YU-NO, like Desire.

Of course it also reminds me of YU-NO itself (why I decided to play it, actually). It has a branching narrative with a flowchart for the player to follow and fill out, point-and-click gameplay (no controller support here), and some puzzles to solve. The puzzles are not true narrative puzzles but rather the “embedded” kind described above; interestingly, YU-NO’s puzzles are not like this, rare for a Japanese game; they are inventory based (occasionally raw information based, like Ayumi’s ending revealing the location of the jewel hidden next to the hypersense stone in the laboratory, or a branch of Kanna’s path informing the player that the report page Ayumi is missing can be found in the bushes near the lab) rather than dependent on arbitrary flags and are more like puzzles I would expect from a North American or European 90s adventure game.

Still Synesthesia does a good job marrying its puzzle and gameplay elements with its story, which focuses on a mystery regarding the origin of psychic abilities. It delves into mathematical and science topics, as well as anthropology and even mythology while still maintaining a near-future sci-fi setting. There’s also a light romance element.

Anyway yeah, on the YU-NO influence, there is this mysterious and secretive teacher character (Keller), who I imagine has to be inspired by Eriko, right? I mean I don’t know for sure, but it seems like it.

One of the game’s bad endings also resembles a bad ending from YU-NO quite a lot with its staging.

Well, Synesthesia is blatantly inscribing itself into the continuum of Japanese adventure games, and I guess it knows its history, to its immense credit. Like how near the end the player must navigate an underground (actually underwater, here) maze, a genre staple since the Famicom edition of Portopia Renzoku Satsujin Jiken. I respect Synesthesia for that quite a lot.

It desperately needs a proofreader though. The game is available in one language, that being English, but it clearly either was not written by a native speaker or was written first in another language and then translated into English. It’s not to the point where the game is unenjoyable, but often the way characters phrased their lines was weird, with word choice that felt off. Some words were consistently misspelled. And most noticeable and irritating of all, the overwhelming majority of lines in the game, whether dialogue or narration, contain at least one comma splice. Like, not even kidding. It was rarer in my (100%) playthrough of the game that I saw a line without a comma splice than a line with one. Do people really not know how to use commas and periods properly? I guess not. Anyway, the game was still enjoyable, but that was a major flaw.

Overall I guess I’ve just been in an adventure game type of mood lately. A true SF adventure or narrative game like Kojima’s two would be nice to queue up next. Spire Games, the developers of Synesthesia, also have an earlier game called The VII Enigma, and it seems to fit the bill. So maybe I’ll try that out.